Thrilling Tales to Get in the Spooky Spirit

As the leaves turn and the weather changes, it’s time to carve pumpkins, pick out costumes, or read thrilling tales. In the lead up to Halloween, we’ve pulled together a list of thrillers that will keep you turning the pages. As always, we’re focusing on the hidden gems that our readers loved, and hope you will, too.

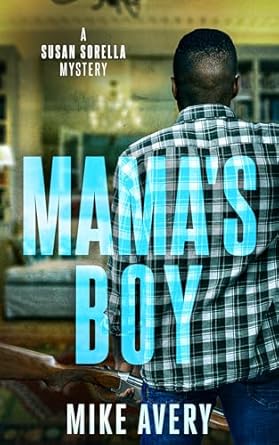

Mama’s Boy by Mike Avery

With over 20 reviews and a 4.8 star average, Mama’s Boy by Mike Avery is the third and final book in the Susan Sorella series. This series chronicles Susan Sorella, a defense attorney, as she attempts to save her client from life in prison.

In Roxanne D.’s five star Amazon review, she raves of this installment, “A senior in high school who finally worked up the nerve to ask the girl he had a crush on out, and she said yes. Imagine his joy. Imagine going home and falling asleep only to be awakened by gunfire. Imagine finding your father shot to death and as soon as you pick up the gun, the cops burst in and arrest you for the murder of your father.

This is a very well written book that keeps you on the edge of your seat. You think you know what is going to happen, but no – something else happens. Held my attention from the first page to the last!”

Robert F. concurs in his five star Amazon review. “…As a storyteller, Avery has created an array of colorful characters operating in the always-tribal City of Boston. Where else would an Italian mob boss demand a meeting to threaten an Irish street gangster to lay off a Black liquor store owner? The characters, their motives and the scene settings always ring true. The drama builds naturally, concluding in the masterful trial scenes. The outcome remains in doubt until the jury returns to the courtroom with its verdict. Happily, the real end of this story is knowing that Susan has been called to take on her next case and no doubt our fourth story. Can’t wait..”

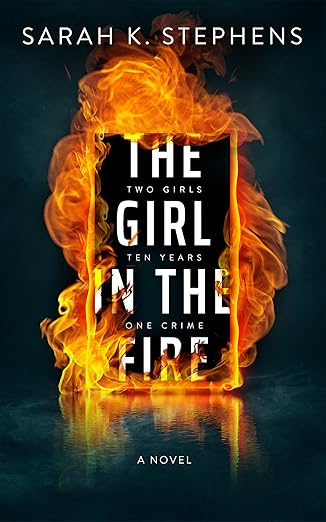

The Girl in the Fire by Sarah K. Stephens

With over 90 reviews, this psychological thriller follows Damien, as he untangles the lies of his fiance, before it’s too late.

“The Girl in the Fire is one of those books that grabs you and doesn’t let go until the last page. Sarah K. Stevens has crafted a twisty, turny rollercoaster of a story that had me guessing at every chapter,” Smaltz writes in their five star Amazon review. “The storyline is incredibly unique, with two different viewpoints that kept the tension high. The way it’s told really made me feel like I was inside the characters’ heads—never knowing who to trust. And let me tell you, that sense of not knowing who’s on your side made it such a page-turner. I was glued to it! The characters were so well written; they felt real, complex, and deeply flawed in the best possible way…”

Nicolette raves in her five star Amazon review, “What an introduction to Sarah K. Stephens The Girl in the Fire was! This story is like a snowball. It starts out just rolling along and building up, but as it gets bigger it starts going faster and faster. This snowball takes many turns as it’s flying down the hill on an unpredictable path. And at the bottom, the snowball smacks into its conclusion and all the individual pieces find their final resting place. I loved the character development and arch of this novel, and you will too!”

The Cobalt Curse by Joey O’Connor

With over a dozen reviews, and an outstanding 4.9 star average, The Cobalt Curse is a globe spanning thriller that follows Professor Kai Baldwin as he searches for his missing former fiance.

Lynne G. writes in her five star Amazon review, “This is an excellent book and story, loved it, could not put down. Fast paced with many twists and turns, intrigue created with intelligence, knowledge of many places, languages, viruses, peacekeeping, travelling the world, from Dubai to the Congo jungle. I could picture myself there and it opened my eyes to the many issues of conflict materials, human tragedy, abuse and child labour; very sad this goes on today. I would like to see this book in movie form, it would make a blockbuster movie. Kudos to Joey O’Connor. Cannot wait to read another by this author!”

Alison K. raves in her five star Amazon review, “Right out of the gate The Cobalt Curse and its intriguing storyline grabs the attention of readers. Who is this professor with scars across his wrist that seem to be whistleblowing on the so-called smartphones that dictate everyday lives? What does this have to do with children in the Congo? You’ll find out right quick because The Cobalt Curse is a page-turner and the plot will drive you to get to the bottom, the very bottom, of this suspenseful spin on the nefarious culture of modern day technology. The Cobalt Curse moves through the lives of protagonists and antagonists alike at bullet speed as the words become a moving picture from fade in to fade out.”

Dead Water by Berrick Ford

With over 200 reviews and a 4.5 star average, Dead Water is the first of a three book series, which takes place in Cornwall. In this first installment an investigative team works to get to the bottom of a suspicious death on the beach. According to the Publisher’s description this one is perfect for fans of Ann Cleeves, Kathy Reichs and Simon McCleave.

“If, like me, you enjoy watching English detective TV series (Vera, Midsomer Murders, Blue Lights…) then you should definitely try this book…I thoroughly enjoyed it and can’t wait to read the next story in this new, exciting crime thriller series,” Peggy M. raves in her five star Amazon review. “…The writing was fluent, The crime was slowly uncovered, it was very exciting and remained a mystery until the end. The author did a great job of explaining how the police worked in England, the different names and many other things involving police work..”

Lola L. concurs in her five star Amazon review, “This beautifully written story of a new police officer on the Cornish coast brings the reader in with its flawed and honest characters and harsh and wild setting. Tamsin Poldhu and Rob Rego become unlikely partners and even friends as they solve the murder of a young woman washed up on the beach of Tamsyn’s hometown. With dueling viewpoints of the outsider and the hometown girl, we grow to love the town even as we hate the crime.”

Five Man Fugue by C.D. Peterson

With a dozen reviews, and a 4.2 star average on Amazon, Five Man Fugue is a mystery told from five different, and seemingly unrelated, viewpoints.

NanaP. writes in her review: “This book was so unique I can’t even give it a good brief summary just know if you love a good mystery/romance/literary fiction then you will definitely enjoy this book because most of the time it is one or all three of those genres. All I can say is wow… What a freaking book!”

htyll7 agrees in their five star Amazon review, “…Clever and insightful with a riveting storyline and rich characters, you’ll be on the edge of your seat all the way to the last page.”

Hidden Gems readers got to read these terrifying novels first, so if you want more books that make your heart and mind race, sign up today! Subscribers to Hidden Gems receive invitations to read books like these – plus other titles from any of up to 15 other genres – for free. Authors send these out in the hopes that the readers will write an honest review once they’re done.